The Clausewitz Homepage frequently receives requests for graphics. This page describes our policies for use of our own graphics and provides information and links to sources for graphics copyrighted by other organizations. Please let us know if you are using our graphics—we may want to link to your site or list your publication.

This is the central directory page for the "Clausewitz Graphics" section of Clausewitz.com. Other pages in the section include:

• Clausewitz: The Authentic Portraits (includes important derivatives)

• Historical Depictions

• Caricatures

• 3D/Sculpture

• Humor & Cartoons

• Souvenirs

• Miscellaneous

• Images of A-H Jomini

• Clausewitz's Military Decorations

Clausewitz.com Corporate WebGraphics

Images visible on The Clausewitz Homepage™ are all optimized for display on the web. Therefore, they are relatively low-resolution and sometimes not suitable for printing. Please visit our Contact page to send copyright permission requests.

Clausewitz.com™ usually permits the use of any graphic on the Clausewitz website not specifically identified as belonging to someone else, with the following exception and proviso: The image to the left (in all variations) is the Clausewitz.com corporate logo, which can be displayed only if the display includes a clear indication of its corporate identity, i.e., an embedded link to https://clausewitz.com and/or the clear label "Clausewitz.com." This logo is based on a photo of the bronze bust of Clausewitz owned by the National War College, in Washington, DC.

ClausewitzStudies.org™ The image to the left (in all variations) is the ClausewitzStudies.org logo, which can be displayed only if the display includes a clear indication of its organizational identity, i.e., an embedded link to https://ClausewitzStudies.org and/or the clear label "ClausewitzStudies.org." This logo is based on the marble bust of Clausewitz owned by the German Historical Museum in Berlin, Germany.

Most of the images of books appearing on Clausewitz.com webpages, especially those appearing in the Clausewitz Bookstore, are from Amazon.com. Amazon holds copyright.

CLAUSEWITZ: THE AUTHENTIC PORTRAITS

and

Important Derivative Images

There are now four known portraits of Clausewitz (three of them surviving as original works), possibly only two done from life. The existence of a fifth is also recorded—an official portrait (currently lost) done by the famous German artist Franz Krüger. Most modern portrayals are derived—with widely varying methods, skill, and integrity—from the (1830?) portrait by Wilhelm Wach, described as portrait #3 below.

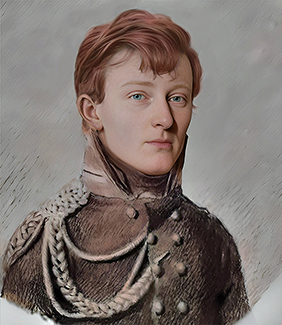

1. The first, dubbed "The Young Clausewitz"

This is a new discovery, supplied in 2015 to Bernd Domsgen and Olaf Thiel of the Clausewitz Society (Freundeskreis Clausewitz) in Burg by descendants of Clausewitz's siblings. Vanya Bellinger suggests it dates from c.1808-1810.

This version was created in 2023 using Fotor AI's "Old Photo Restorer" and portrait colorization tools (plus a fair amount of manual customization) to produce a synthetic photorealistic image. It is ©Clausewitz.com 2023. Click this image to see a larger one.

It is possible that this picture was drawn by Marie v. Brühl herself. Her artistic skills are demonstrated by the portrait painting directly below the new drawing, which is Marie's 1815/16 portrait of General Graf August von Gneisenau (Clausewitz's mentor and friend). As you can see, it is quite well done, though perhaps a little too realistic (i.e., non-heroic) for popular taste. [DHM data]

Gneisenau

Gneisenau

by Marie von Clausewitz

[Click for larger image.]

2. The second portrait (below) shows Clausewitz in a Russian lieutenant-colonel's uniform (c.1813 or 1814).

The location of the original portrait, originally in the possession of the Clausewitz family, is unknown. However, old B&W photos of the original and a couple of rather poor, primitive-looking copies exist. Both the drawing of the young Clausewitz shown two pictures above and the painting shown below may have been done by Marie von Clausewitz. This is the opinion of Marie's biographer, Vanya Bellinger, based on the timing and on Marie's demonstrated competence as a painter.

The image shown below-left is a b&w photo of the original portrait from ASMZ [Allgemeine Schweizerische Militärzeitschrift], a Swiss military publication. ASMZ indicated that the image had come from a photo in Werner Hahlweg, Klassiker der Kriegskunst (Darmstadt 1960), p.256. It also appeared in Kurt von Priesdorff, Soldatisches Führertum (Hamburg 1937-1942), 10 Bände, picture of Clausewitz, Karl Philipp von, Bd. 5,65, nr.1429. There is a poor copy at the Führungsakademie der Bundeswehr, which is discussed further below.

The middle picture below was created by processing the ASMZ photo, which is very dark, with Fotor's AI Photo Editor. This image is ©Clausewitz.com. Click on the image to see the printed b&w photo.

The picture below-right was made in October 2023 using Fotor's AI Photo Editor, starting with the b&w image from Priesdorff's book. It took about 3 minutes.

To get a better idea as to the appearance of the original painting, we processed the Priesdorff image through Fotor's AI Photo Editor, using its "Old Photo Restorer" tool and a bit of manual correction. Click this thumbnail to see a larger image.

The painting on the wall below is a copy of the lost portrait showing Clausewitz in a Russian lieutenant-colonel's uniform. This copy was given to GeneralMajor Beck, commandant of the Führungsakademie of the German Bundeswehr, when he visited the Russian Military Academy in 2005. The photo below that, taken by Vanya Eftimova Bellinger but heavily processed to bring out detail, minimize glare, and correct for perspective distortion, is of the copy that hangs in the Clausewitz Museum in Burg.

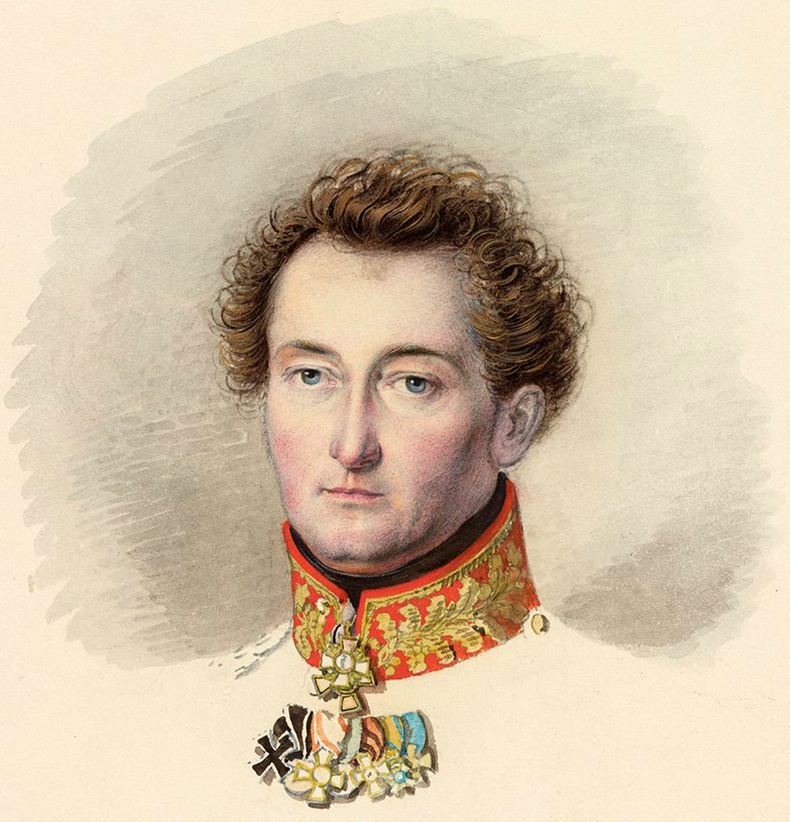

3. The third portrait of Clausewitz: The Wach Portrait

This is the original full-color portrait by Wilhelm Wach (who had also painted a famous—and surprisingly erotic—portrait of Queen Luise of Prussia). Three particularly authentic versions of it are shown below. Wach's portrait of Clausewitz was supposedly painted from life in 1830, but it may in fact be a posthumous portrait based on earlier drawings. The painting itself is very small, 26x21 cm. In the West, it was long thought lost or destroyed during World War II, but it had been expropriated from Marie's aristocratic family descendants by the communist Deutsche Democratic Republic (DDR; East Germany). It was then given to a suitably proletarian recipient. It is now back in the hands of the Clausewitz family's relatives.

This is the most frequently-encountered image of Clausewitz, appearing in many forms and derivatives. Black and white images are often derived either from photos of the original painting or from various copies of the color lithographs (shown below), prints of which vary widely in quality, coloration, and general appearance. Numerous additional drawings, de novo paintings, and posterizations have been made based on or "inspired by" these historical images (see further below).

A color lithograph made by a rather obscure painter and engraver, named Franz Michelis (1762–1835)—or by his son, who was evidently a student of Franz Krüger. The artist clearly worked directly and precisely from the original painting by Wach. Genuine prints of this lithograph vary a great deal, owing to the technology of the time. Click the image to see an enlarged detail.

This image was sent to Clausewitz.com from the former East Germany in 2001, marked with the photographer's copyright. The anonymous senders indicated that they possessed the original painting, so we refer to it as the DDR version." The image was cropped as shown. Oddly, it makes it appear that Clausewitz is out in a rainstorm, with individual raindrops beaded up on the painting's surface. Based on information recently received, it appears that this was caused by reflections on protecting glass. Click this thumbnail to see a larger image.

The image above is one of Clausewitz.com's preferred images of the Wach painting. It is a faithful composite, fundamentally a merge of transparent overlays using several different images of the original, rather pastel Wach painting. One such overlay superimposed the stronger contrasts of a B&W image of the color lithograph made by Franz Michaelis. The whole has been slightly re-colorized using Fotor AI tools. This composite is ©Clausewitz.com 2016/2023. If you wish to use it, on the web or in print (we have higher-resolution versions), you must request permission through Clausewitz.com.

The image below, a slightly modified version of the picture used in Clausewitz.com's 23 x 35-inch color poster, is based instead on the DDR version of the Wach painting. It very closely follows the original (and may in fact be the original, in digitally processed color with some modern enhancements.) It too utilizes a transparency containing the stronger contrasts of a B&W image of the color lithograph made by Franz Michaelis. Click this thumbnail to see a larger image. This composite is ©Clausewitz.com 2005/2023.

4. The fourth portrait (c.1825, shown below) is by Johann Jakob Kirchhoff. The following discussion is edited and abridged from Vanya Eftimova Bellinger's interesting article (which goes into issues far beyond mere art appreciation), "A Portrait of Carl von Clausewitz as a Senior Officer: The Question of Military Regulations and the Role of Routine and Creativity in Military Conduct," The Strategy Bridge, 2 JAN 2023.

A newly discovered painting, now in the collection of the German History Museum in Berlin, promises to shed new light on Clausewitz's life. It comes from the collection of the German Historical Museum in Berlin. Several years ago, the institution acquired the partial estate of the artist Johann Jakob Kirchhoff (1796–1848). Among the sketches and studies found was an aquarelle [transparent watercolor] of Carl von Clausewitz. The drawing was part of an 1825 series of portraits of Prussian officers and statesmen who had played a significant role in the 1813–1815 campaigns against Napoleon. Kirchhoff's portrait of Clausewitz unmistakably reminds us of the image by Wilhelm Wach. A possible explanation is that, after Clausewitz's death, Marie wished to commission a portrait of her husband that could be turned into a lithograph, printed, and gifted to close friends. She was dissatisfied, however, with a recent official portrait (now lost) done by the famous German artist Franz Krüger. Marie intended to commission another painting, an amalgam of Krüger's work and a drawing she possessed that, according to her, truly captured Carl's facial expression. The similarity between Kirchhoff's image and Wach's famous portrait of Clausewitz suggests that the former might have been that drawing. This also implies that Wach's work was created posthumously by working the facial expression from Kirchhoff's image onto Krüger's portrait.

Compared to portrait #1, Clausewitz's 1825 gaze is solemn. Fifteen years and the impact of several wars are no doubt reflected in the two images, but in 1825 Clausewitz's health was also at a low point. His letters from that time describe prolonged and severe pain in the throat that made it impossible for him to swallow and enjoy food and drink. Hence the unhealthy complexion and weariness evident in his face.

Johann Jakob Kirchhoff, Carl von Clausewitz, 1825 (copyright: German Historical Museum/Deutsches Historisches Museum).

Johann Jakob Kirchhoff, Carl von Clausewitz, 1825 (copyright: German Historical Museum/Deutsches Historisches Museum).

Clausewitz.com Editor's note: We certainly agree that the Wach image is derived from Kirchoff's watercolor. If we overlay the two (and rotate the Wach image half a degree clockwise), the faces line up perfectly. (Though the helix of his ear looks a bit fuller and resemble the one in the 1814 painting.) Wach has, however, de-aged Clausewitz considerably, removing the puffiness and thickening the hair, etc. Overall, his Clausewitz looks flushed and healthy. The slight rotation towards the vertical makes him seem more alert and energetic.

To us, however, the facial expressions seem quite different. Kirchoff's subject seems to have his mind on something else—his wan gaze goes somewhere beyond us and slightly to our left. Wach's Clausewitz seems forthright but searching and reserved. He gazes firmly and directly at us. One can easily imagine this as Marie's vision of him. The DDR photo of the Wach painting seems subtly benign, with a slight smile that verges on Mona Lisa's, which may account for Clausewitz.com's preference for it.

The (allegedly 1830) Wach painting (portrait #3) is clearly derived from the 1825 watercolor by Johann Jakob Kirchhoff (portrait #4). When overlaid as a transparency over the 1814 image, neither of those paintings can be lined up with its facial features. Still, in all of these pictures we are very clearly looking at the same man.

To see images and a discussion of Clausewitz's military decorations, click on the image below.

A slick but flawed 1999 effort to re-create the Wach portrait (larger)

Above is a very slick new version, though the face is considerably altered and we don't care for it. This painting is a 1999 copy based on old photos of the Wach portrait, at the time thought lost in World War II. It was commissioned by the Clausewitz Gesellschaft and presented to the Führungsakademie of the German Bundeswehr in Hamburg in that year. We took this file from http://www.cominganarchy.com/archives/2005/11/16/god-of-war/, but that page has disappeared. Since the face really does not look like that of the actual Wach portrait or other authentic paintings, etc., we regard it as non-canonical.

A misuse of artwork: Immediately above, the Clausewitz on the right is from the portrait commissioned by the Clausewitz Gesellschaft in 1999. But the editors for USMA's Modern War Institute have gone to a lot of trouble to alter the eyes and mouth to make the Clausewitz on the right look much sterner and tougher. This version appeared as an illustration to Steve Leonard's "'You Really Think I'm Irrelevant? LOL.' A Letter to Clausewitz Haters from Beyond The Grave," West Point: Modern War Institute, USMA, 6 May 2020. While Leonard's article is obviously pro-Clausewitz, the distortion of a specific individual's portrait to reflect a stereotypical view of Prussian generals (which is particularly misleading in this case) is not a recommended practice. To put it politely. It's just as distorted as the image below—albeit in a little more targeted sense.

Above we see the 1999 Clausewitz Gesellschaft portrait head inserted into another painting and used as the cover illustration of one of many Russian reprints [ISBN 9785699664863] of the 1934 Russian translation of Vom Kriege. The version used at the top of the "Clausewitz Graphics" page has been modified—it uses a portrait head derived directly (digitally) from the original 1830 Wach painting; the excessive gold trim on the uniform coat's lower half has been removed. (Click on the image above to see a larger image of our version.) This image is OK as a metaphor on the cover of Vom Kriege—the older Clausewitz pictured is the author of that book, which certainly discusses the Russian campaign of 1812–13. Any image that wishes to recall the younger Clausewitz who actually fought in Russia, in Russian uniform, should use the portrait painted c.1814, as in this rendition.

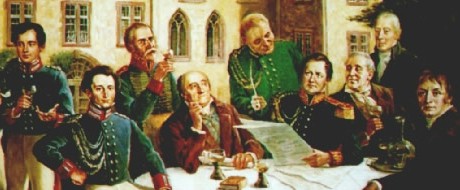

ANOTHER VARIATION ON WACH: The portrait seen below is a detail from the painting "Die Tafelrunde" by Josef Schneider (1966), which shows Clausewitz drinking with some prominent comrades in Mainz in 1815, when Clausewitz would have been about 35. It is displayed on the Clausewitz Homepage by courtesy of the Headquarters of the German Army Forces Command, Koblenz (HQ GARFCOM). They hold the copyright and have been known to supply high-quality photographs of it to facilitate high-quality print reproduction. It is based on a mirror-image of the Wach portrait.

A fellow named Oliver Schmidt tells us that the painting was made as a gift from the municipality to the Bundeswehr corps command in Koblenz in commemoration of the 150th anniversary of the existence of an army corps headquarters in the town. The painter, Josef Schneider, was living in the village Emmelshausen (25 km south of Koblenz) and got 3500 DM for his work. Schmidt cites Rüdiger Wischemann dissertation "Die 'Tafelrunde im von-der-Leyenschen Hof': ein Koblenzer Tafelbild von Josef Schneider, Emmelshausen" (Berlin, 2003), ISBN: 3898257576.

Here's a thumbnail of the whole painting. Click this thumbnail for a larger (1500 pixels wide) image.

For a list of who's who in this painting, click this image.

Here's a detail of the main group.

The Schneider portrait of Clausewitz is a mirror image of the Wach/Michelis image.

Jomini and Clausewitz

Jomini and Clausewitz

(©Clausewitz.com 2018)

Jomini is often portrayed as Clausewitz's "opposite." They certainly sniped at one another in print, but their relationship at the theoretical level was far richer and more complex than that label implies. They read each other's works very carefully and each incorporated much of the other's argument. Clausewitz's criticisms of Jomini are aimed at his early work. Jomini's most famous book, The Art of War, was written after Clausewitz's death and after Jomini had read his work.

(Click here for info on the picture above and for more images of Jomini.)

(Jomini morphing into Clausewitz.)

(Jomini morphing into Clausewitz.)

MARIE VON CLAUSEWITZ

Clausewitz's wife—and the posthumous editor of Vom Kriege—was Marie von Clausewitz, born Marie Sophie Gräfin [Countess] von Brühl (1779-1836). Any serious understanding of the personality and thinking of Carl von Clausewitz must include his deep relationship with his high-born, well educated, well connected, and politically sophisticated and passionate wife. The image below derives from a lost painting done sometime after 1800. The original source for this image is a b&w lithograph commissioned by her cousin after her death. It comes to us from Karl Schwartz's book, Leben des Generals Carl von Clausewitz und der Frau Marie von Clausewitz, geb. Gräfin von Brühl: Mit Briefen, Aufsätzen, Tagebüchern und anderen Schriftstücken (Berlin: Ferd. Dümmlers Verlags-Buchhandlung, 1878). Her cousin reported that this was a good likeness, but he felt that the eyes were not quite correct. We created the colorized version below in October 2023, using Fotor's AI Photo Editor. (Click for a larger image.)

The rather frumpy-looking bonnet she is wearing is actually a political statement—it is a "bonnet a la Nelson,” i.e., a fashionable celebration of the British admiral Lord Nelson’s 1798 victory in the Battle of the Nile. Given Prussia's nervous neutrality at the time, this would have been a strong and somewhat risky statement at court.

The image below is a detail of an 1815 portrait of Countess Marie von Clausewitz by artist François-Joseph Kinson, late court painter to Jérôme Bonaparte, King of Westphalia. At the time he was urgently in need of new patrons. Marie was uncharacteristically overweight at the time, evidently a nervous reaction to that year's excitements, but she couldn't resist the opportunity.

Clausewitzian "Trinity" demonstration device

The "Trinity" is a key concept in Clausewitzian theory, which Clausewitz illustrated by referring to this scientific device. You can obtain the ROMP (Randomly Oscillating Magnetic Pendulum) from science toy stores for about $30. (It's easy to remove the extra magnets shown here.)

Availability: This item is distributed (wholesale) by Supertek Scientific. You can buy it (retail) at Dabnis Scientific & Industrial. It is also listed on Amazon.com (USA), but is often unavailable there.

For other graphic visual metaphors for Clausewitz's Trinity, click here.

PRINT-QUALITY GRAPHICS

AKG-IMAGES

AKG (see contact info below) can provide either transparency, print or high-res scans (356 DPI, .jpg not .tiff format) of the color lithograph portrait in either color or black & white. Charges will depend on your intended use, number of copies to be reproduced, etc. These images are thumbnails. They have other relevant images as well.

AKG London Ltd

https://www.akg-images.co.uk/

5 Melbray Mews

158 Hurlingham Road

London

SW6 3NS

UK

Tel: +44 (0) 20 7610 6103

Fax: +44 (0) 20 7610 6125

email: [email protected]

If you are outside the UK, Ireland, the USA, Canada, Australia, New Zealand or Hong Kong, please contact the Berlin office:

Archiv fur Kunst und Geschichte

Teutonenstrasse 22

14129 Berlin

Germany

Tel: +49 (0) 30 80485200 Fax: +49 (0) 30 80485500

If you are in France, please contact the Paris office:

AKG Phototheque

67 Rue Notre-Dame des Champs

75006 Paris

France